2000 Generations One Race: Homo Sapiens

Now Playing: Y-chromosome and mtDNA tracers

Most scientists today agree that Homo sapiens -- modern human beings --originated in Africa some 200,000 years ago, and that between 60,000 and 100,000 years ago, small groups began migrating out of Africa and spreading out across the continents.

Over time, these groups of migratory humans became isolated from one another, and eventually mutation and other evolutionary pressures produced slight genetic changes, some of which are responsible for the differences in appearance we've commonly used to divide up human beings into racial groups. But periods of isolation were followed, as trade and transportation were developed, by periods of admixture -- the mixing of populations that had previously been separate.

A map of the migrations of early humans, as reconstructed via DNA studies.

By tracing slight changes in DNA and by combining that data with a calculation of the rate at which genetic material changes over time, researchers have been able to reconstruct the general pattern of the historical migrations of peoples across the globe, starting in East or South Africa and extending north into Europe and Asia and eastward to the Pacific Islands and through the Americas, to the tip of South America.

The research indicates that all humans alive today share a couple of common ancestors, a woman who lived in Africa around 150,000 years ago (with the 1st~ mtDNA marker), and a man who lived in Africa around 60,000 years ago (with the 1st~ Y-chromosome marker), at around the time human beings began to leave Africa to explore the rest of the world.

Considering that commonality, it's no surprise the amount of variation between even the most disparate groups of human beings is very small. It's estimated that people share some 99.9% of their DNA. Even looking at that .1% that does vary, 85% of the variation that has been observed is unconnected to membership in any particular group of people; only 15% of the variation is between defined groups. In fact, because as a species we spent the most time in Africa, the greatest amount of genetic variations are currently found among people living on the African continent -- on a genetic level, an individual of East African ancestry may have more in common with a European than with a West African.

Since the differences that separate groups of humans are truly miniscule -- amounting to a little more than one-tenth of one-tenth of a percent of the entire human genome -- researchers into the genetics of populations have to work with extremely minute variations in the code of life.

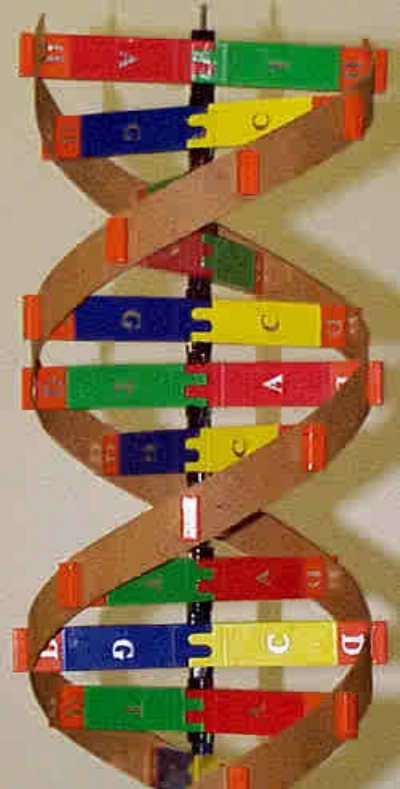

What they look for are genetic markers known as "single nucleotide polymorphisms" or SNPs (pronounced "snips"). These are single-"letter" variations, where one of the four bases that make up DNA -- adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), or thymine (T) -- is substituted for another at a specific point within a known gene. In particular, scientists look for and document SNPs whose frequency varies widely between different population groups.

These SNPs are referred to by scientists as being highly "informative," that is, they correspond to differences in ancestry, though they may not be within the genes that code for skin color, nose shape, hair texture, or any of the other physically observable characteristics we think of as indicating race.

While the actual science is quite complex, and depends heavily on statistics and information theory, one can think of a group of SNPs that occur together -- that is, they seem to be inherited together as a group -- as making up a "haplotype," and a group of haplotypes as a "haplogroup."

When the SNPs in question are highly informative -- that is, they have been observed to occur noticeably more often in one or more population groups than simply among human beings in general, they can be used to make deductions about the history of populations and the heritage of individuals.

Basically, these informative markers (and groups of informative markers linked in haplotypes and haplogroups) can be used to infer ancestry and linked to particular regions of the world or estabilished lines of descent, then simple DNA testing can be used to make surprisingly clear deductions about what sort of genetic heritage a particular person might have -- the very premise behind AFRICAN AMERICAN LIVES.

A map of the general distribution of genetic markers informative of ancestry among populations worldwide.

The map of admixture test results above shows both the variation and commonality among the world's population groups.

Four common groups of genetic markers are shown on this map: Blue indicates the markers found most widely in Europeans; maroon sub-Saharan Africans; beige East Asians; and aqua Native Americans. As you can see, there is a fair amount of shared genetic information among today's human beings -- even the "purest" African, Native American, East Asian, and European groups (marked with "P"s on the map) bear the genetic legacy of encounters with other groups.

While haplogroups are not directly analogous to races or ethnicities, certain haplotypes and haplogroups are observed more frequently in some groups of people than others. It's possible, in some sense, to think of these haplogroups and haplotypes as branches of the human family tree.

It's a far more complex and varied type of tree than 19th century theorists of race had in mind -- a better image to keep in mind might be a dense, intertwined network of roots, with new shoots springing up from a number of intersections.

Remember, over the course of human history populations have gone through periods of isolation and intermixing, so the difference between groups is largely a matter of different statistical frequencies of variations from an agreed-on standard, not a radical difference.

There is a biological dimension to what we understand as race, but it differs from the simplistic, linear understanding of racists who have sought to ground their ideologies in science. Looking at the human genome, race is nearly as complex a biological concept as it is a social one.

The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey by Spencer Wells

Around 60,000 years ago, a man--identical to us in all important respects--lived in Africa. Every person alive today is descended from him. How did this real-life Adam wind up father of us all? What happened to the descendants of other men who lived at the same time? And why, if modern humans share a single prehistoric ancestor, do we come in so many sizes, shapes, and races?

Showing how the secrets about our ancestors are hidden in our genetic code, Spencer Wells reveals how developments in the cutting-edge science of population genetics have made it possible to create a family tree for the whole of humanity. We now know not only where our ancestors lived but who they fought, loved, and influenced.

Informed by this new science, The Journey of Man is replete with astonishing information. Wells tells us that we can trace our origins back to a single Adam and Eve, but that Eve came first by some 80,000 years.

We hear how the male Y-chromosome has been used to trace the spread of humanity from Africa into Eurasia, why differing racial types emerged when mountain ranges split population groups, and that the San Bushmen of the Kalahari have some of the oldest genetic markers in the world.

We learn, finally with absolute certainty, that Neanderthals are not our ancestors and that the entire genetic diversity of Native Americans can be accounted for by just ten individuals.

It is an enthralling, epic tour through the history and development of early humankind--as well as an accessible look at the analysis of human genetics that is giving us definitive answers to questions we have asked for centuries, questions now more compelling than ever.

ResourcesAccording to the multi-regional model, an archaic form of humans left Africa between one and two million years ago, and modern humans evolved from them independently and simultaneously in pockets of Africa, Europe, and Asia.

Wells' work and that of others confirms the more widely accepted Out of Africa model, which says that all modern humans evolved in Africa and then left in several waves of migration, ultimately replacing any earlier species.

"Genetic evidence tells us that Homo sapiens are of recent origin and arose in Africa," said S. Blair Hedges, a molecular biologist at Pennsylvania State University.

"African populations have the most ancient alleles [gene pairs that code for specific traits] and the greatest genetic diversity, which means they're the oldest," Hedges explained. "Our species probably had arisen by 150,000 years ago, with a population of perhaps 10,000 individuals."

Chris Stringer, director of the Human Origins Program at the Natural History Museum in London, said: "The multi-regional model of Homo sapiens evolving globally over a long time scale is certainly dead."

Whether archaic humans and modern humans interbred is another point of debate. "Given the uncertainties, it isn't yet possible to establish whether we are entirely recent African in origin 'certainly my preference' or whether there was a little bit of hybridization/assimilation" between modern and archaic species," said Stringer.

Wells says there is no genetic evidence that supports the idea of intermixing, and several DNA studies actually argue strongly against it.

Today, there is general agreement that Homo erectus, the precursor to modern humans, evolved in Africa and gradually expanded to Eurasia beginning about 1.7 million years ago.

By around 100,000 years ago, several species of hominids populated the Earth, including H. sapiens in Africa, H. erectus in Southeast Asia and China, and Neandertals in Europe.

By around 30,000 years ago, the only surviving hominid species was H. sapiens.

But when did we leave Africa and where did we go? Here's where opinions diverge widely.

Wells says his evidence based on DNA in the Y-chromosome indicates that the exodus began between 60,000 and 50,000 years ago.

In his view, the early travelers followed the southern coastline of Asia, crossed about 250 kilometers [155 miles] of sea, and colonized Australia by around 50,000 years ago. The Aborigines of Australia, Wells says, are the descendants of the first wave of migration out of Africa.

Many archaeologists disagree, saying the fossil record shows that a first wave of migration occurred around 100,000 years ago.

"Archaeological evidence suggests that there were modern humans in at least two places in the Levant region of the Middle East 90,000 years ago," said Alison Brooks, a paleoanthropologist at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. "They disappear from the Levant about 10,000 years later, but could have survived further south in Asia? We just have no evidence."

"There's evidence of Homo sapiens in Australia 60,000 years ago, and they'd have to go through India and Southeast Asia to get there."

Wells agrees that there may have been early human forays into the Middle East, but argues that the Levant of 100,000 to 150,000 years ago was essentially an extension of northeastern Africa and was probably part of the original range of early Homo sapiens. These early settlers were replaced by Neandertals in the region about 80,000 years ago.

"There's a roughly 30,000-year gap in the archaeological record of Homo sapiens outside of Africa," said Wells. "The real expansion occurred in the Upper Paleolithic (around 40,000 years ago) into the uncharted territory of Asia proper."

Brooks agrees there's a gap, but puts it closer to 20,000 years.

Richard Klein, an anthropologist at Stanford University, has one explanation for the gap and the subsequent waves of colonization beginning around 45,000 years ago.

Klein thinks Homo sapiens may have been anatomically modern 150,000 years ago, but did not become behaviorally modern until about 50,000 years ago, when a genetic mutation related to cognition made us smarter.

He theorizes that this change in thinking ability enabled modern humans to craft sophisticated tools, build permanent lodgings, hunt more effectively, and possibly develop language. It also led to greater travel.

Other possible triggers for the burst of migration 45,000 years ago include an increase in population, which spurred competition and innovation; a change in diet, with consumption of more meat and fish; the acquisition of language; and climate change.

Populating the Globe

Wells says a second wave of hominids left Africa around 45,000 years ago, reproduced rapidly, and settled in the Middle East; smaller groups went off to India and China.

Isolated by mountains and the sea for many generations, and exposed to a colder climate and less sunlight than in Africa, the Asian populations became paler over time.

Around 40,000 years ago, as the grip of the Ice Age loosened and temperatures briefly became warmer, humans moved into Central Asia. Amid the bountiful grassy steppes, they multiplied quickly.

"If Africa was the cradle of mankind, then Central Asia was its nursery," said Wells.

Around 35,000 years ago, small groups left Central Asia for Europe. Cold temperatures kept them there. Cut off from other groups, these migrants became paler and shorter than their African ancestors.

From there, around 20,000 years ago, another small group of Central Asians moved farther north, into Siberia and the Arctic Circle. To minimize physical exposure to the extreme cold they developed, over many generations, stout trunks, stubby fingers, and short arms and legs.

Finally, around 15,000 years ago, as another Ice Age began to wane, one small clan of Arctic dwellers followed the reindeer herd over the Bering Strait land bridge into North America.

According to the genetic data, says Wells, this initial group may have included as few as two or three men, perhaps 10 to 20 people in all. Also isolated, they too acquired distinct physical characteristics.

Many archaeologists, however, believe that Australia, the Middle East, India, and China were inhabited much earlier.

"The dates don't compare well to the order or the geography of the migration patterns revealed by the fossil record," said Brooks. "Y-chromosome data give consistently younger dates than other types of genetic data, such as mitochondrial DNA."

Hedges said that "the dates of expansion and colonization discussed by Wells may be correct, but they almost appear to be too recent. Most geneticists are getting data that agree with most archaeological and fossil data." He noted, however, that all of the different methods used for dating can generate errors.

"If you step back a bit and look at the bigger picture, there is a lot more agreement in this field today than there was a decade ago," Hedges said.

"There's almost certainly not an Adam or Eve," said Tishkoff. "Each of our genes have their own history, which could be passed on from different ancestors. It's more likely that a lineage can be traced back to a population of 50, 100, or even several thousand people." Others agree.

"The fact that one man apparently gave rise to the Y-chromosome genes of all moderns does not mean he was our only male ancestor," said Stringer. "What it means is that his male progeny were more prolific breeders or luckier, and their Y genes survived while those of his contemporaries didn't. But those contemporaries could have passed on many other genes to present-day peoples."

That's "absolutely correct," said Wells, adding: "The real significance of the date of our common Y-chromosome ancestor, is that it effectively gives us an upper limit on when our species began to leave Africa."

One point of wide agreement among those who study human origins is that more and more insight will come from closer collaboration between disciplines.

"Greater discussion and collaboration between geneticists and paleoanthropologists would be good for both," said Stringer.

"It's worth bearing in mind," he said, "that studies of recent DNA are studies of the genes of the survivors. Such studies can't tell us anything about non-survivors, such as the Neandertals and Solo Man in Java. We still require fossils, archaeology, and, where possible, ancient DNA for the whole picture of human evolution."

Wells's work described in Journey of Man draws on genetics, palaeoanthropology, palaeoclimatology, archaeology, psychology, and linguistics.

"I really see the field as a collaborative, synthetic effort to make sense of our past," he said. "The notion that any single area of investigation, operating in isolation, could have all the answers is ludicrous."

National Geographic Human Origins Resources

Posted by philcutrara1

at 3:56 PM EST

Updated: Thursday, 16 March 2006 11:07 AM EST

We are bombarded every day with conflicting information about our health. Is it better to eat a low-carb diet or a balanced diet? Should we be physically active three times a week or five times a week? And how can we be expected to follow any of these recommendations when we're always so busy?

We are bombarded every day with conflicting information about our health. Is it better to eat a low-carb diet or a balanced diet? Should we be physically active three times a week or five times a week? And how can we be expected to follow any of these recommendations when we're always so busy?

We are meditating on peace, light or bliss while the express train is constantly moving. Our mind is calm and quiet in the vastness of Infinity, but there is a movement; a train is going endlessly toward the goal. We are envisioning a goal, and meditation is taking us there.

We are meditating on peace, light or bliss while the express train is constantly moving. Our mind is calm and quiet in the vastness of Infinity, but there is a movement; a train is going endlessly toward the goal. We are envisioning a goal, and meditation is taking us there.

In contemplation everything is merged into one stream of consciousness. In our highest contemplation we feel that we are nothing but consciousness itself; we are one with the Absolute. But in our highest meditation there is a dynamic movement going on in our consciousness. We are fully aware of what is happening in the inner and the outer world, but we are not affected.

In contemplation everything is merged into one stream of consciousness. In our highest contemplation we feel that we are nothing but consciousness itself; we are one with the Absolute. But in our highest meditation there is a dynamic movement going on in our consciousness. We are fully aware of what is happening in the inner and the outer world, but we are not affected.